Summary and results: I unexpectedly discovered that my reaction time improved after I was prescribed metformin (brand name: Glucophage) for pre-diabetes. Metformin is typically used to lower blood sugar, though it also has other physiological actions. Since researchers have demonstrated a connection between reaction time and cognitive function, my results suggest that metformin may have nootropic effects. This finding is novel and, if confirmed by other studies, opens up new potential applications for metformin—a medication already considered something of a wonder drug, with reported benefits extending to aging, longevity, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases (see, for example, the recent review, “Metformin: Is it a drug for all reasons and diseases?“).

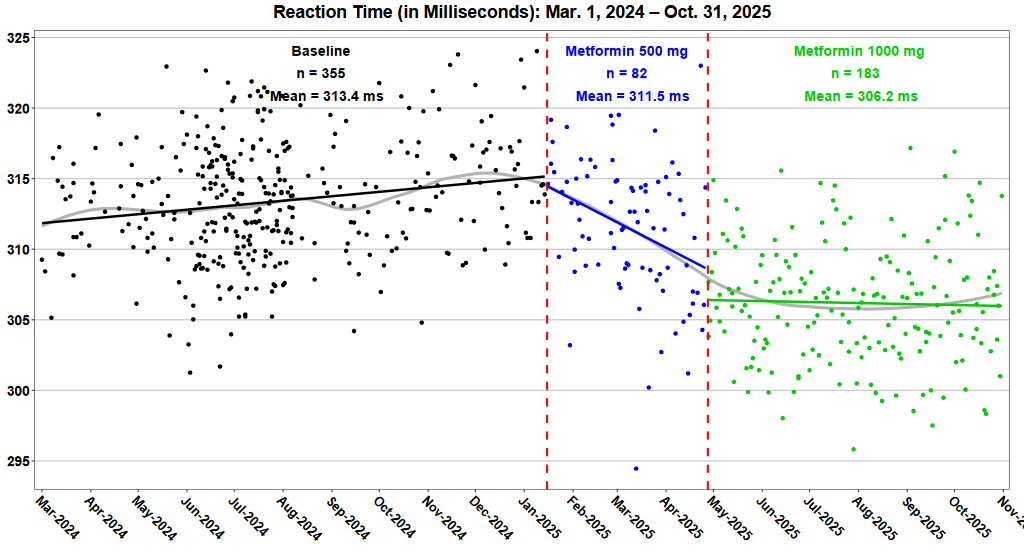

The following graph tracks my reaction time (RT) over three periods: a relatively long pre-treatment baseline, roughly three months taking 500 mg of metformin daily, and about six months on 1000 mg metformin. Each data point represents a testing session conducted using an app running on my Windows PC (the testing protocol is described in more detail further below). The black, blue, and green lines are linear regressions. The gray curve represents a locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curve fitted to all the data points. Note that lower values are better in the sense that they represent faster reaction times.

The data plotted above is available as a CSV file, aggregated by individual testing session. The raw data (minus incorrect trials) is also available.

The pre-treatment baseline includes data gathered during a self-experiment I had conducted during the summer of 2024. I was testing the effects of creatine supplementation and measuring my reaction time three times each day. I found very little, if any, improvement in my RT scores.

Background: In January 2025, I was diagnosed with pre-diabetes. Although my blood sugar levels were only slightly above the range of what’s considered normal, I was prescribed metformin. I took 500 mg (in an extended release formulation) daily for about three months. Not long after starting the metformin, I noticed that my RT scores started improving—a result that was all the more impressive, given that my scores were trending slightly upwards (slower) prior to starting metformin. Three months of treatment didn’t result in a substantially lower blood sugar, so my doctor increased the dose to 1000 mg daily. My scores continued to improve for a few weeks after the increased dosage but have since largely plateaued. This positive effect persists as of this writing (Nov. 2, 2025).

This result was completely unexpected. When I began taking the metformin, I didn’t even consider the possibility that it might affect my RT. Also, I was largely unaware of metformin’s wide-ranging reputed benefits, though I did hear of its putative effects on longevity. There were no other obvious changes in my life that could have explained the improvement in my speed. I didn’t alter my diet, change my exercise habits, or start/stop any other medications or supplements. I think it’s quite likely that the improved RT scores resulted from the metformin and not some other cause.

How was reaction time measured? I measured my reaction time every evening, using a Windows app that I wrote (it’s open-source and available for download). After I completed my creatine study in the summer of 2024, I continued performing the reaction time test daily, just to maintain my skills. The specific testing protocol was developed by the late psychologist (and noted self-experimenter) Seth Roberts. Each testing session consists of 35 separate trials, where the app displays a random digit between 2 and 8, inclusive. The subject’s task is to hit the corresponding key as quickly as possible. Incorrect responses are not counted, and each digit is presented five times (in random order) during a testing session. Each session takes approximately three minutes to complete.

This type of protocol is known as a “choice reaction time test”, meaning that the experimental subject is required to select and execute the correct response from multiple options when presented with various stimuli. This type of test is often used to evaluate decision-making speed and cognitive processing abilities. Choice RT is considered more cognitively demanding and correlates more strongly with general intelligence.

Why measure reaction time? Research has demonstrated a well-established correlation between RT and measures of cognitive ability, including, most notably, IQ. A comprehensive meta-analysis by Sheppard and Vernon (2008) examining 172 studies with over 53,000 participants found consistent negative correlations between reaction time and intelligence, with correlations ranging from -0.22 to -0.40 depending on task complexity. These correlations stem from studies where the RT and cognitive measures are averaged across populations of subjects. It’s perhaps less established that RT can be used to track changes in cognitive performance within a single individual over time, but it seems plausible – and Seth Roberts theorized that this was a valid approach. His own “n=1” experiments further reinforced his view.

Before his untimely death in 2014, Roberts was promoting the idea that reaction time could be used by self-experimenters to track their brain health and to test the effects of various interventions. His plan was to help establish a distributed community of people who would all conduct self-experiments using RT as a metric. I collaborated with him on studies of caffeine, soy, and flaxseed oil, but I stopped working on it after he died. However, after a long hiatus, I was prompted to revisit this project after I read an interesting post on Scott Alexander’s Substack page.

Alexander posted a long list of putative nootropics ranked by their effectiveness, as gauged by a survey of users. Asking people, “Did substance X improve your cognitive performance?” may produce some useful leads on what works and doesn’t work. My goal, however, was to find an assessment method that is more objective, where changes in reaction time can be used to estimate differences in effectiveness. My earlier study on creatine was my first attempt at this strategy.

Metformin’s effects on my blood sugar Something that’s curious about my results is that my RT scores improved considerably despite the fact that the initial dose of metformin (500 mg daily) had at most a small effect on my blood sugar. When I tracked my glucose via a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) for two-week stretches, the average dropped by just 2.4 mg/dL after I first started taking the metformin. The diagnostic tests ordered by my doctor (fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1C) didn’t budge at all. Raising the metformin dose up to 1000 mg daily had a larger effect, though it was still relatively modest.

| Continuous glucose monitor, 2-week avg. |

Fasting glucose from hospital lab |

A1C from hospital lab |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-metformin baseline | 107.6 mg/dL | 108 mg/dL | 5.7% |

| Metformin 500 mg daily | 105.2 mg/dL | 108 mg/dL | 5.7% |

| Metformin 1000 mg daily | 100.6 mg/dL | 104 mg/dL | 5.5% |

These glucose results raise the question of the mechanism by which metformin may have improved my reaction times.

Metformin and reaction time: Possible mechanisms of action Metformin has been available in Europe since the 1950s and in the United States since 1994. In the US, it’s approved as a first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes. In my case, I was prescribed metformin for treatment of pre-diabetes, even though the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not officially approved it for this indication.

Metformin’s exact mechanisms of action are still being researched. Metformin’s main effect, or at least the effect with the greatest clinical relevance, is to lower blood glucose levels. It’s possible that reaction time is sensitive to glucose levels, performing best within a narrow blood sugar range. Certainly, diabetes is known to be associated with mild cognitive impairment, and diabetics have more than a 50% higher risk of developing any type of dementia. In my case, my blood sugar was only slightly elevated above the normal range, but perhaps a small improvement in blood glucose produced a measurable boost in my reaction time.

Metformin has multiple physiological effects, some likely stemming directly or indirectly from blood sugar changes, while others may be mediated through entirely different pathways. The following is an incomplete list of some of metformin’s metabolic effects:

- Reducing hepatic glucose production: Metformin decreases the liver’s output of glucose, particularly by inhibiting gluconeogenesis

- Improving insulin sensitivity: It enhances peripheral glucose uptake in muscles and tissues

- Activating AMPK: It activates AMP-activated protein kinase, a cellular energy sensor that affects metabolism

- Effects on gut microbiome: Emerging research suggests it may also work partly through altering gut bacteria and affecting glucose absorption

Note that there are varying amounts of support for these effects, and some have only been demonstrated in animal models. In recent years, metformin has generated considerable interest for its potential to slow aging and extend lifespan. Of particular note is a possible beneficial effect on neurodegenerative diseases.

Did I notice any practical improvements in cognition? The short answer is “no”: I didn’t notice any obvious differences in concentration, memory, or performance under cognitive load. However, the fact that I didn’t observe anything doesn’t necessarily mean that there were no practical effects. Would you notice if you became, say, 3% smarter over the course of several weeks? During my earlier creatine experiment, I did attempt to track my cognitive performance by recording self-assessments at the end of each day. However, I found it difficult to perform this task in any sort of objective manner. When I reflected back on a day’s activities, I found it hard to put a number on how well I performed cognitively. I felt that each day was more or less the same as every other day, with maybe just a handful of exceptions when I performed exceptionally well (or poorly). Having said all this, I still think that cognitive enhancement is a worthwhile goal to explore, even if improvements are difficult to notice.

Next steps: I will continue taking the metformin indefinitely, and I expect to keep measuring my RT daily. As a follow-up project, I might start taking creatine supplements to see if I can get my reaction time to become even faster. My earlier creatine study was compromised by insufficient creatine doses and too short a supplementation period. I can address those deficiencies with a new study on creatine.

Addendum: Richard Sprague is the author of the “Personal Science” Substack and another collaborator of the late Seth Roberts. Richard wrote up an excellent analysis of my experimental data, using various statistical tests. If you’re at all interested in personal science / n=1 studies, you should subscribe to Richard’s Substack.

Collaboration: Please contact me if you’re interested in collaborating on self-experimentation studies.

Leave a Reply